By Caitlyn French for MLive

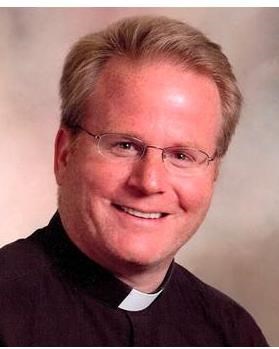

Eric B. English died of a heart attack Saturday, Jan. 23, 2021, at McLaren Bay Region Hospital. He was 54 years old.

“He loved journalism and he loved the practice of journalism, and that will be his legacy,” said John Hiner, vice president of content for MLive, who worked with English for nearly three decades.

English was born in Wyandotte, Michigan, on March 18, 1966, and graduated from Trenton High School, later attending the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. After he graduated from Northwestern in 1988, he was hired by The Bay City Times in Bay City, Michigan, and ran its Tawas City bureau until 2007, when he became a business reporter for the paper.

He later served as an assistant community editor for The Saginaw News and The Bay City Times from 2009 until 2012 and as a managing producer from 2012 through 2016. In 2016, he served as the news leader in MLive’s Ann Arbor News office until returning to Saginaw and Bay City in 2018.

English’s wife, Kathy English, emphasized her husband’s dedication to journalism and the variety of work he did during his career. She recalled that he once flew on a B-52 that was set to be retired and he also scored a ride with the Navy’s Blue Angels flight team.

“There’s just so much that he did and covered in news, I have notebooks and notebooks and notebooks full of his articles that he saved from day one,” Kathy English says.

Outside of work, English was an avid outdoorsman who enjoyed hunting, fishing and gardening. Kathy English refers to him as a regular Johnny Appleseed and says he really enjoyed the ‘Up North’ life.

Eric English was more than a journalist and lover of the outdoors — he was a dad through and through. His daughter, Holly, 23, says her father was quite supportive of her ideas and endeavors and that he would often ‘adopt’ her friends, who tended to call him their second dad.

“What I’ll remember most about my dad is he always gave 110% of himself to whatever he was doing, whether that be working on a story or being a dad,” Holly English says.

In 2012, the English family lost their son and brother, 10-year-old David, after a 19-month battle with a brain tumor.

Many of English’s co-workers and former colleagues recalled fond memories of his presence and dedication in the newsroom while expressing their grief over the loss.

Former Bay City Times editor Rob Clark worked side by side with English and refers to him as one of his closest friends. The two were making plans to reconnect this summer if restrictions eased from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Eric was one of the smartest, most talented people and journalists that I’ve ever known,” Clark says. “This guy was a total workhorse and he knew how to manage people. He knew how to get the best stories, he could write, he could edit. He was just a phenomenal guy to have on your team, to have as a teammate.”

Clark adds, “Just an amazing person, an amazing human being gone way, way, way too soon.”

English served as a mentor for numerous reporters throughout his career. Reporter Cole Waterman reflected on the impact that English left and what it will be like moving forward.

“Simply put, I can’t yet fathom the idea of working without him, without his guiding presence. I expect I’ll feel like a ship without its rudder,” Waterman says. “He will leave an Eric-shaped void that will be impossible to fill.”

Waterman recalled his first interaction with English back in 2009, which set the stage for a long-standing camaraderie.

“I was awkwardly sitting at my newly assigned desk, nervous as hell, feeling over my head with imposter syndrome, when he walked over, shaking his head in his uniquely world-weary way,” Waterman says. “I don’t think he even introduced himself as he started talking to me, grumbling about this and that as though I’d been a longtime colleague of his. Weirdly, his brusque manner put me right at ease.”

Colleague Bernie Eng echoed similar thoughts on English’s unique but endearing mannerisms and the impact he had.

“In the years I’ve known him, Eric didn’t sugarcoat a darn thing, and he wouldn’t want me to now,” Eng says. “But I watched that cranky and cynical façade make him one of the most compassionate and caring people I’ve ever met. His love and concern for his family, coworkers, staff and the communities and people he and his staff reported about is unsurpassed. Eric truly made a difference.”

Despite MLive’s staff working at home since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, English still managed to bring smiles to the faces of staff during digital meetings.

“Working from home the past few months has been hard for our MLive crew,” says Kelly Frick, senior news director for MLive. “But there wasn’t a day when Eric didn’t make all of the editors around the state laugh with a good one-liner in our morning chat. Personally, having worked closely with him for all of my career, I am struggling to imagine life without him.”

https://www.mlive.com/news/saginaw-bay-city/2021/01/veteran-journalist-remembered-for-dedication-to-his-craft-and-his-family.html