Well, I never thought of the military as an option. But somehow, because I signed up for ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps) as a freshman at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina, I found myself in olive drab military gear and boots with a rife on Thursday afternoons… marching around the college’s football field. It doubled as where we learned how to march in formation, and to a cadence. None of us were particularly good at it. After all, we were liberal arts students studying to become businessmen (no girls at Wofford in the 1960s), lawyers, doctors, educators and even some clergy. Wofford had its roots in the Methodist church.

After four years of marching and receiving a monthly ROTC check of about $50, those of us in the class of 1969 were given an option of which part of the U. S. Army we wanted to join. We all would begin active duty after graduation as second lieutenants, better than being drafted as an enlisted man… or so we were told. All of us seemed destined for Vietnam – President Lyndon Johnson’s unpopular war in Southeast Asia.

I chose the transportation corps. Infantry was nowhere near my list. I think signal corps was my second choice. My brief encounter with infantry training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, during the summer of my junior year left me underwhelmed. Actually, more than underwhelmed. Can’t find the word to describe my experience. Negative probably is best. One encounter that I will always remember is the 40-yard low crawl – an exercise that requires you to crawl on your belly without raising your butt. I “got” to do it three times in a row because I could not keep my butt down. On the third attempt, I was the only one crawling and exhausted. The rest of the camp – hundreds of ROTC types – watched. When I finally finished successfully, on the third try, the entire camp erupted into a resounding cheer and applause. I was dead tired, and a bit embarrassed. So much for the infantry.

Graduation from Wofford took place in May 1969. I received my degree – a Bachelor of Arts – in English. Had no idea what to do with it. I’d think about it while serving my required two years on active duty. At graduation, in addition to my diploma, I received my gold-color second lieutenant bars.

I did get assigned to the transportation corps and received my orders for Fort Eustis in Virginia. That is the headquarters for the transportation corps. There, in addition to rolling out of bed every morning at 6 o’clock, calisthenics in shorts and T-shirts were required rain or shine, hot or freezing cold. Then, after jumping jacks, pushups and a quarter mile run, you had to do several pullups before being admitted to the mess hall for breakfast. I think that was the coldest I have ever been.

While completing my transportation corps officers training, I got my orders to report to Fort Polk in Louisiana. Yes, some place warm. I was assigned to – of all things – an infantry battalion. Our mission was to train troops headed to Vietnam. Being an English major, our unit commander gave me the job of developing lesson plans for those giving combat instructions.

A desk job, which wasn’t bad until the unit commander – a major – told me, to go serve as an attorney to prosecute a soldier who had gone AWOL (absent without leave). I had no benefit of training to do this, but in the army if you are an officer – even a second lieutenant — you can serve as an attorney. I did some quick study, asked questions and took on the assignment. Everything went smoothly, until the military judge asked me for the day book. No one had said anything about having the day book with me. That is the book that logs soldiers out to go off post. When I tried to explain that I did not have it, the judge went ballistic. He told me that the case was being dismissed and that my unit commander should never ever appoint another officer to prosecute an AWOL case without providing him with the day book. He made an example out of me. I never served as a military attorney again, and was glad about that.

I eventually got my orders for Vietnam. I was somewhat relieved since Fort Polk was – and probably still is — the arm pit of army bases. It is stuck in the middle of nowhere Louisiana. However, on a couple of occasions I did venture down about 200 miles to New Orleans where I learned about crawfish – a Cajun delicacy. To this day, I will choose crawfish over shrimp.

Before being shipped overseas, I was given a few days leave at home in Laurens, South Carolina, where my parents and brothers lived. I was there for maybe a week before going to Charleston where my first flight was from the Charleston Air Force Base to Washington, D. C. Then it was Flying Tiger Airlines to Alaska to Japan and on to Vietnam. It was well over 20 hours flying time. On the final decent, I felt like we were dive-bombing into the ground – standard procedure to avoid enemy fire. We landed safely.

I reported in at Long Binh – the major command headquarters for the United States Army Vietnam. I am sure I spent the night in barracks there, but I am fuzzy on most details except for when I actually reported for duty. Still wearing my summer kakis and in one of the headquarters buildings, I waited for the officer who was going to give me my in-country assignment. To my surprise a female colonel entered the room. I stood at attention. Saluted.

She said I was being assigned to a truck company supporting an infantry battalion. Not having much military bearing, I – without hesitation – asked her what else she had. Looking surprised, she said she was not normally asked that question. However, since this was her last day in country and she was going back to the states the next day, she asked how much I knew about boats. Again, without hesitation, I told her I knew as much about boats as I knew about trucks.

In actuality, I did not know much about either. My preference, though, was to be with one of the army’s two boat battalions instead of in a jeep heading an infantry platoon into Cambodia.

She said, okay. I was told to report to the 159th Boat Battalion at Cat Lai, outside of Saigon. Cat Lai was an old French seaplane port on the Dong Nai River. The French fought the Vietnamese in the late 1940s and early 1950s before leaving.

The two-story stucco buildings in the Cat Lai compound were surrounded by a walled enclosure with guard stations spaced all the way around. I was told that from time to time there had been attacks by North Vietnamese. The major danger, though, was having one of the ships in the Cat Lai harbor blown up by enemy sappers. These ships, often on their last voyage, carried ammunition for our troops. Needless to say, if one of these was ever blown, it would have taken out Cat Lai and part of Saigon. That actually happened after I got back to the states in 1971.

I reported to the 5th Boat Company where I was issued army fatigues, a flak jacket, boots, weapons, a helmet and told that I would be the company’s supply officer. Again, something I knew noting about, but I was all for on-the-job training. It certainly beat riding shotgun in a jeep. The 5th Boat

Company’s mission was to patrol rivers in heavily armed landing craft for combat and logistical purposes. My post was on shore, except for occasions when I was called upon to go on the river to a freighter to inspect its cargo.

My first several days at Cat Lai were spent in bed. I had come down with something that gave me a fever, dysentery and achiness. Since I rarely got sick, this was unusual. I was on my back on a cot in the open air of the building where I had been assigned officer quarters – a room with a door and window, not bad by Vietnam standards. We all shared a communal bath. There were probably two dozen of us on the second floor of the building – all lieutenants and captains.

I was able to start my supply officer duties. Fortunately for me, the supply sergeant – an army veteran — knew all about supply, and we got along terrifically. He liked my lack of military bearing. I just told him and others to call me Lt. Joe. They did when we were among ourselves. Also, it was nice to have at Cat Lai two other Wofford graduates from my class. Not expected since there were only 275 in our class. And here we were, three Wofford men together halfway around the world fighting a war.

The biggest challenge at this stage of the Vietnamese conflict was keeping troops busy. Everything within our control – rations, maintenance materials, clothing and daily supplies – were kept in CONEX containers. We had dozens of them. To keep the six men assigned to supply occupied, we were constantly organizing and reorganizing and reorganizing and reorganizing the containers. It was something constructive to do.

This, however, did not keep all troops content, especially those assigned to river duty. Drugs – the most destructive element of serving in Vietnam in 1970 and 1971 – had many enlisted men hooked. The primary reason was the drugs over there were dirt cheap… pennies compared to what they would cost in the states. We actually had enlisted men “reup” – volunteering for another tour in Vietnam – just so they could afford their drug habits.

In addition to being the supply officer, I was named the battalion’s drug officer and battalion historian. Being historian was interesting. I enjoyed it. Being drug officer was disturbing, especially when we took addicts to the Long Binh hospital strapped down in a jeep to keep them from hurting themselves or attacking me and two other soldiers. I did not enjoy this, but it had to be done. By now, I was a first lieutenant.

I did think about life after military service and thought advertising would be the path to take. A friend of mine at Wofford had entered Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism’s advertising program, and recommended it. It was considered by many to be the best. He edited the Wofford College yearbook before I did. I was editor in 1968. So, I mailed an application and introductory letter to Northwestern.

Some time went by, but I did – to my surprise — get an acceptance letter from the chairman of the Medill School of Journalism Graduate Admissions Committee, Dr. Albert Sutton. There was a stipulation, though. I would have to enter the Medill program in June or wait another full year to begin. I was not scheduled to get out of the army until August. However, I knew the 159th battalion or at least a major part of it was being deactivated in the fall. It appeared the war in Vietnam was beginning to wind down.

Thus, I began writing letters. A lot of letters. I had purchased a Smith Corona typewriter at the PX (post exchange) at Long Binh. I used the old hunt and peck method. Still do.

First, I explained the situation to the 159th command, a colonel and some majors. While empathetic, they said an early out in June rather than the fall was out of the question. It would have exceeded the military’s 90-day early out policy.

Not deterred, I moved my inquiry on up the chain of command… getting the same negative response. I then had the bright idea of contacting my U. S. Senators – Strom Thurmond and Ernest Hollings.

My inquiries required some prodding but eventually I got a positive reply from Senator Thurmond who understood that it made no sense for me to stay with a unit that was being deactivated at a time when I needed to be at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. I informed the Medill School of Journalism that I would be enrolling in June, but instead of entering the advertising program I wanted to enter the journalism program. The chairman of graduate admissions said okay, and they looked forward to me being there on June 18. This was still months away from when I was to enroll.

Duties as the 5th Transportation Company supply officer were pretty much routine, not a lot of excitement. It was not like we were in an active combat zone, even though agent orange was dropped outside our compound on a regular basis to kill the foliage. We did keep our guards up since we were vulnerable to attacks on the ammunition ships in our harbor.

Duties as the 5th Transportation Company supply officer were pretty much routine, not a lot of excitement. It was not like we were in an active combat zone, even though agent orange was dropped outside our compound on a regular basis to kill the foliage. We did keep our guards up since we were vulnerable to attacks on the ammunition ships in our harbor.

One day, though, an enlisted man came running to me near the officers’ barracks. Almost out of breath, he told me I had to go the enlisted men’s barracks because one of the privates had taken a loaded weapon – against all rules – back to his bunk. He told everyone that he was going to shoot the company commander, a first lieutenant who was not well liked, especially by the enlisted men because he – the lieutenant – carried his rank on his sleeve. In other words, he thought he was better than others. The private with the loaded weapon told those concerned that he would only give the weapon to Lt. Joe. I really did not know him, but I had a positive rapport with most at Cat Lai. He said he would only give it to me and no one else. So, I went to the barracks. I was told the soldier had no prior behavior problems. The door was closed. I called out the soldier’s name, and he told me to come in. Of course, he could have shot me. He did not. He gave me the weapon, and I promptly walked it over to the company commander. Slamming it down on his desk, I told him this was a close call but that if he did not change his ways he could become a statistic. I left, and heard no more about the incident. The soldier that took the weapon was not charged with an offense. This was, after all, Vietnam.

Two other hair-raising experiences were later at Cat Lai and then at Vung Tau.

Vung Tau, first. This is a coastal town about 80 miles from Cat Lai. I agreed to accompany a delivery there since an officer was needed for the job. It was a beautiful day. In the states, it would have been a called a beach day, and Vung Tau is a beach. As we got closer to our destination, the driver and I noticed a large crowd gathering between us and the gates of our destination. They were holding signs and sticks. Guards at the gates where we were headed hurried us in. Unbeknownst to us, we had driven into an anti-government demonstration. We made our delivery, had a nice lunch of prawns (very large shrimp) and saw the beach where a freighter had been beached. Our trip back to Cat Lai was uneventful even though we were locked and loaded, just in case.

Speaking of being locked and loaded, the Cat Lai incident required this. One night, actually about 3 am, all of us were roused out of bed, told to put on our flak jackets, helmets, boots and get loaded weapons from the armory. That is where weapons were kept since Cat Lai was not an active combat area. I got my 45 and M-16 and headed, as directed, to the front gate of the Cat Lai compound. Flares were going off everywhere. The company commander about whom I spoke earlier ordered me to take three men and hold down the main entrance. Sounded like a suicide mission to me, but orders were orders. The 5th Transportation Company supply sergeant was next to me, thankfully. He was a calming and reassuring influence. He had been in combat before. I had not. Hours went by. No attack, but the adrenaline was pumping. False alarm, and the only one I experienced while in Vietnam.

As my tour in Vietnam came to a close, a dinner was held at the officers’ mess hall. We had these occasionally. The battalion commander at the end of the meal got up and made a few announcements, some related to the downsizing of the battalion. He then turned the program over to the battalion’s executive officer who called me up front. I was baffled. He then proceeded to hand me two medicine balls, each measuring about a foot in diameter and weighing several pounds. He then began recanting how I had, against all odds, gotten the army to grant me an early out to go to graduate school. Because of my persistence and indefatigability, the battalion senior staff voted to give me its first – and, as far as I know, only –“you really got a set of balls” award. I was speechless but said something stupid like I had enjoyed being at Cat Lai.

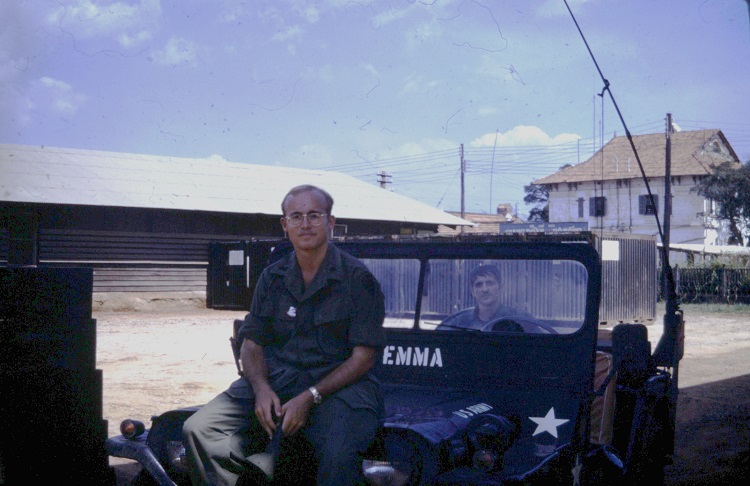

When the day arrived on June 11 for me to head back to the states, I dressed in my summer kakis and was told not to wear my fatigues in the states. I packed some things in my duffle bag, grabbed my typewriter and camera and headed to Emma – the jeep that was assigned to me at Cat Lai. As the driver was beginning to leave the compound, a soldier began running – sprinting – after us yelling at the top of his voice. “Lt. Joe, stop. STOP! STOP!” We did. He, after catching his breath, told me the battalion commander had hoped to personally give me what he was handing me. What he was carrying had literally just come in. I opened the package. It was a bronze star for meritorious service. To this day, I am humbled.

I did make it back to the states. When asked if I wanted to serve in the U. S. Army Reserves, I declined thinking to myself “I have enjoyed as much as I can stand.”

Weighing 128 pounds, I had a week to get from my parent’s home in Laurens, South Carolina, to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. I made it. Not long after arriving in Evanston, I was sitting on the steps of the Northwestern Student Center on Sheridan Road and a student anti-Vietnam war demonstration came marching by. I thought, I was just there.

I graduated from Medill in 1972. I was able to afford it thanks to the GI Bill and several of my economy measures such as living rent free in the basement of a mansion on Sheridan Ave. in exchange for shoveling snow and mowing grass. My mode of transportation was a Sears & Roebuck bicycle which I rode everywhere, even in snow, wind, rain and ice. The Medill librarian noticed that even on the coldest days I wore only a sweater and a jacket. She gave me a heavy coat that someone had left in the library, and I gladly accepted it. I hung on to that coat until a few years ago.

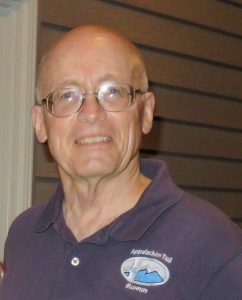

Lessons learned at Medill, especially from Professor Ben Baldwin, and at Cat Lai laid the groundwork for the successful career that I enjoyed in journalism, corporate communications and investor relations. I am happily retired now in Aiken, South Carolina, at age 77. I did recover from an Agent Orange linked heart attack in 2011.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joseph F. Patterson has created and managed proactive communications and investor relations programs for financial services companies (First Atlanta Corporation, Wachovia Corporation and Sterling Financial Corporation), utility services (Westinghouse Electric Corporation, PJM Interconnection and GridSouth), telecommunications providers (Powertel and D&E Communications) and real estate/resort developments (Sea Pines Company and Kiawah Island Company) as well as major nationally televised sporting events – the Heritage Golf Classic, the LPGA Championship, the World Invitational Tennis Classic and the Family Circle Tennis Cup. He began his career as a reporter for the Orlando Sentinel newspaper. Joe graduated from Northwestern University with a Master of Science degree in journalism and from Wofford College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English. While serving as a lieutenant in Vietnam, he received a Bronze Star for meritorious service. He is an Eagle Scout.

What is your current role, and what does it entail?

What is your current role, and what does it entail?

Duties as the 5th Transportation Company supply officer were pretty much routine, not a lot of excitement. It was not like we were in an active combat zone, even though agent orange was dropped outside our compound on a regular basis to kill the foliage. We did keep our guards up since we were vulnerable to attacks on the ammunition ships in our harbor.

Duties as the 5th Transportation Company supply officer were pretty much routine, not a lot of excitement. It was not like we were in an active combat zone, even though agent orange was dropped outside our compound on a regular basis to kill the foliage. We did keep our guards up since we were vulnerable to attacks on the ammunition ships in our harbor.